5. Opsterland's rich cultural landscape: Landscape, villages and people

In this chapter we discuss the stratification and construction of the landscape. We first describe how the landscape was created without the influence of human hands. For the basis for the present-day landscape lies for the most part in the ice ages. Then we will look at what traces human hands have left in the rich past history of the present landscape. Starting in the Middle Ages, for example, the peat reclamations resulted in important landscape interventions. This also led to the founding of settlements, of which our current 16 villages are a result. Next, we will give a brief description of those villages and finally, for each village, we will discuss the DNA of the Opsterlander; the uniqueness of the population.

5.1. Landscape of Opsterland

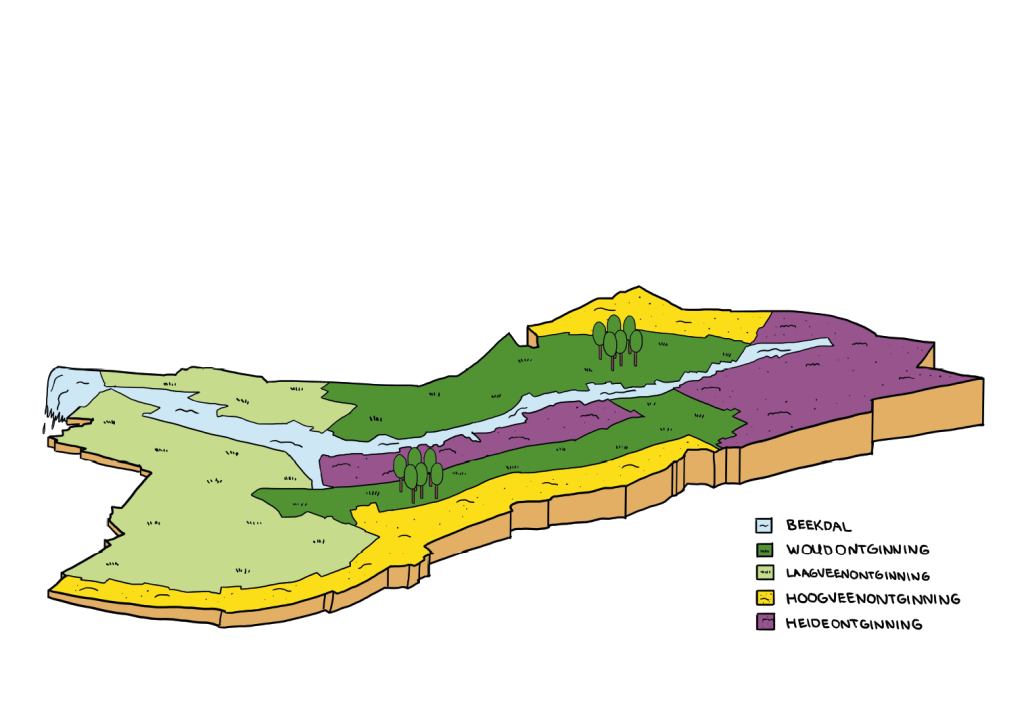

The cultural landscape of Opsterland is the result of centuries of interaction between man and nature. Natural geological processes have shaped the large-scale outlines of the landscape. The results of this are partly still visible today, but are also partly underground. The municipality lies at the transition from the Fries-Drentse boulder plateau to the low-lying moorland of Friesland. The valley of the Koningsdiep (Alddjip), already formed in the penultimate ice age, forms the connecting element between east and west, between high and low, between sand and peat, between villages and people and between the different landscapes.

Beginning in the Middle Ages, man has left an ever-increasing mark on the landscape. During this period, the blueprint of today's cultural landscape was created. The landscaping was usually highly dependent on local conditions such as subsoil and hydrological conditions. For example, Opsterland still had extensive raised bog complexes in the Middle Ages. From the Koningsdiep, these bogs were reclaimed. The typical elongated parceling of land in the municipality is a remnant of this. In later periods, new layers were continually added to the Opsterland cultural landscape. Among the defining cultural-historical formative periods were the wet and dry peat extraction, the large-scale construction of country estates and the reclamation of moorlands. All these developments created a highly stratified and particularly rich cultural landscape.

1. The natural landscape

The large-scale outlines of the landscape as we encounter it today were formed by natural geological processes. During the penultimate glaciation (Saale glaciation), the last glaciation (Weichsel glaciation) and the Holocene, the natural landscape took shape. The Pleistocene landscape was formed during the last two ice ages. This was followed by the warmer and wetter epoch in which we still find ourselves today: the Holocene.

1.1 The Pleistocene landscape

As a result of the prevailing ice flow direction during the Saale Ice Age, the stream valley from Koningsdiep to Beetsterzwaag has a northeast-southwest orientation. The same applies to the boulder plateau on either side of the stream valley. In the subsequent Weichsel Ice Age, the landscape was shaped by the prevailing northern polar winds. On the boulder clay plateau, sandy ridges and expanded lowlands (this later formed the dobs) emerged. The ridges took over the older northeast-southwest orientation as it were. At the end of the Weichsel Ice Age, ice mounds also developed in the landscape, which left large circular craters after melting: pingoruins.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Incised stream valley Koningsdiep

- Boulder clay heights, cover sand ridges and shifting sand heads (Bakkeveenster Duinen, Wijnjeterper Schar)

- Pingor ruins (Turkenleech, Waskmar), dobs (Gânzemar, Siegerswoudster Lake) and pingorelian fringes

- Relief differences (Lippenhuisterheide, Hemrikkerscharren, Wijnjeterper Schar, Duurswouderheide, Bakkeveensterduinen, De Mersken)

- Flint sites, archaeology

- Sandhead Olterterp

- Former valley De Draît

- Koningsdiep: fluvoglacial esker (formed as a result of glacial meltwater) and gravelly sands

1.2 The Holocene landscape (bog landscape)

Due to sea level rise and water stagnation of the boulder clay subsoil, large-scale peat formation occurred during the Holocene. During the maximum peat expansion in the early Middle Ages, almost all of Opsterland was covered with raised bog, even the lower western part of the municipality (drowned raised bog). At that time, the Koningsdiep was a meandering peat river that served as a drainage way of the water coming from the bogs and lakes in the peat (lake stables).

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Koningsdiep as a meandering peat river

The natural raised bog landscape such as the Fochtelooërveen, with peat domes and lake stables has completely disappeared. Remnants of these peat deposits can still be found under church mounds such as those of Lippenhuizen and Wijnjewoude (Wijnjeterp).

1.3 Groundwater flow

At a depth of about 60 to 100 meters, Opsterland has a deeper groundwater flow. This flow is roughly caused by the higher position of the Drents Plateau on the east side of the municipality and the lower lying peat and lake area on the west side. Groundwater flows slowly from east to west and once fell as rainwater on the Drents Plateau. The water travels for hundreds of years before it arrives within the borders of Opsterland. The water is clean and, due to the enormous pressure in low areas, sometimes surfaces as seepage water. Because of the quantity and quality and by filtering, the water is ideal as groundwater for water extraction. The area is far from the sea so there is hardly any salinization.

2. Man's first visible influences on the natural landscape

From the time that man settled permanently in the area that is now the municipality of Opsterland, the area was increasingly occupied. The natural bogs and peat domes naturally drained into the Koningsdiep. In the Middle Ages, agricultural developers used this relief to cultivate the peatlands. From the late 10th century, this reclamation history started from Oldeboorn.

2.1 The agricultural peat extraction landscape (entire municipality)

By the 12th century, the agricultural peat extraction that started from Oldeboorn had already reached the area around Bakkeveen. Perpendicular to a peat stream or river, the exploiters dug ditches into the marshes at even distances. Around such an excavation block, side and rear dikes were constructed, also called piping dikes, against water flowing in from the raised bog. The peat farmers built farms on the peat and could cultivate it temporarily, mainly with rye. Because of the drainage towards the Koningsdiep, the top of the peat came dry, after which it began to oxidize. Because of the resulting drop in ground level, the cultivated land began to sink and a division in the landscape arose. In the eastern part of the municipality, the sandy landscape began to resurface. In the stream valley and in the west, however, the sandy subsoil was much deeper. Due to land subsidence, these landscapes were subject to rewetting. Soon the raised ditches were drawn further into the untouched higher peat bog. Because of this reclamation method, elongated plots of land with ribbons of farms perpendicular to them (settlement axis) were created everywhere along the Koningsdiep and its tributary the Wispel. Every farmer had his own driveway. Except for the younger peat villages, all villages in Opsterland originated in this way.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Stretching parcelization (landscape blueprint)

- Settlement ribbons, settlement axes (disappeared farmsteads, old cemeteries, hamlets, old homesteads)

- Side and rear dikes: piping dikes

- Medieval footpaths and church paths

- Open

2.1.1 The forest landscape to the east: wooded banks and heathland

On the sand, the linear parcelization continued to exist. The big difference with the lower area is that on the higher sandy grounds, wooded banks and hedgerows arose along the linear plots. This enclosed landscape is further characterized by small-scale woods, moorland on sandy ridges, dobby or pingoruïnes and the characteristic northeast-southwest oriented settlement axes and roads.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Wooded banks and canals

- Small-scale woodlands and heathlands

- Settlement ribbons, settlement axes

- Inner and outer roads

- Leidijken

- Iekenhiemen (green farmyards with oak trees)

- Closed

2.1.2 The mieden landscape to the west: the hay meadows

In the western part of the municipality and in the stream valleys, it was much wetter. Many of these lands were completely flooded during the winter months. These lands were usually used as hay land, also called mieden or marschen (mersken). This landscape was particularly concentrated on both sides of the Koningsdiep and its former tributary the Wispel. For better drainage and water storage, the hayfields were often provided with an intricate pattern of ditches.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Hay fields (mieden, marschen, mersken) and hay roads

- Dikes (including along the Koningsdiep, Leppedijk)

- Fine-grained ditch pattern (ascending and transverse ditches)

- Meanders Koningsdiep and Wispel (Alde Ie).

- Foreboards, bridges, wood or til

- Open

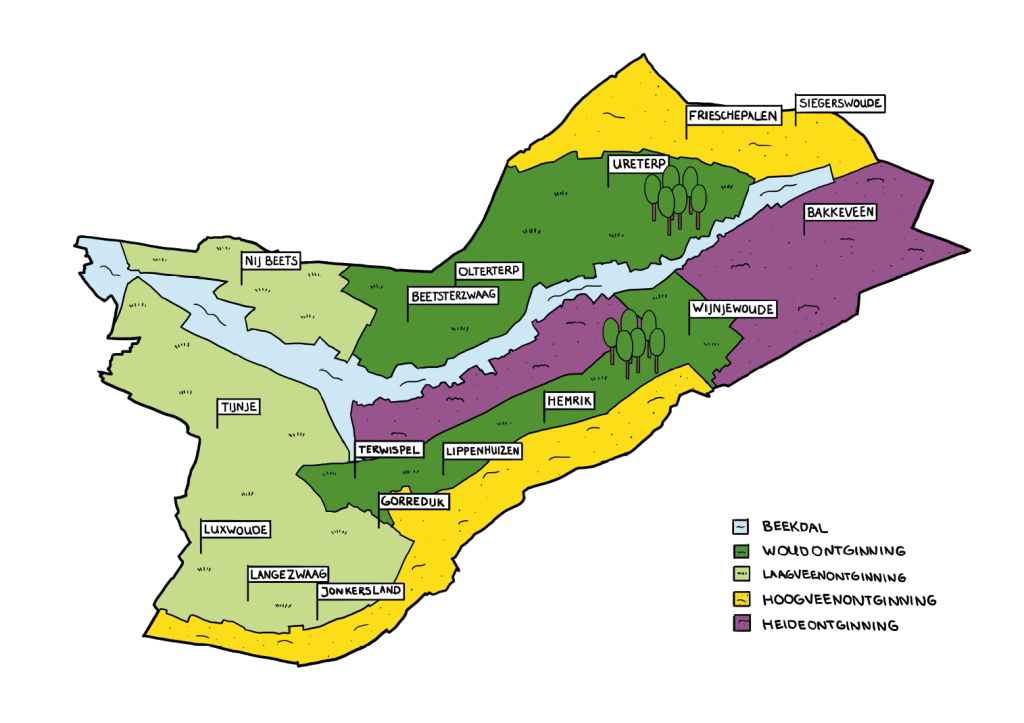

3. Current landscape types.

Due to further increases in scale, population growth, changes in water management and new techniques in agriculture, various landscape types have emerged from the forest landscape just mentioned in the east and the mieden landscape in the west. These are further explained in this section.

3.1 High bog extraction landscape

The uplifting plots from the Koningsdiep river border the municipalities of Smallingerland and Westerkwartier to the north and the former Schoterland (now municipality of Heerenveen) to the south. At the very back of these parcels in the 17th and 18th centuries were still virtually untouched bogs. A contiguous system of piping dikes prevented water from flowing out of these bogs. The peat layers were locally as much as three to four meters thick. For centuries, this peat bog was used almost exclusively for small-scale peat cutting.

3.1.1 High bog mining

Beginning in the 17th century, investors, merchants and prominent Frisian lords bought up these bogs to extract peat. This involved 'dry peat extraction'. By digging canals and embankments, the raised bog was drained. The peat could then be cut off above the water table. The raised bogs in the north were cut from the then Ureterpster canal. In the south were the Schoterlandse compagnonsvaart with districts to Langezwaag and Jonkerslân and the Opsterlandse compagnonsvaart.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Canals and transects with elongated ribbon structure

- Districts and cross-districts with elongated ribbon structure

- Dikes and levees

- Locks, bridges and lock keeper's houses

- Open

3.1.2 Peat colonial landscape

The heavy peat work was performed by many peat laborers. Most of the peat laborers came from elsewhere. They settled along the canals and built a (temporary) shelter there. In this way new settlements arose such as Frieschepalen, Ureterp aan de Vaart (former hamlets Dalen and Pietersburen) and hamlets named after former locks (vallaat) such as Wijnjeterper Vallaat and Hemriker Vallaat. After the reclamation of the peat lands, small plots of land were created. Between the neighborhoods a landscape developed with small-scale block allotments.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Occupation along canals (peat-colonial village with ribbon development)

- Keuter ontginningen between districts and cross-districts

- A planned block or rectangular subdivision

- Alder sedges as field boundaries

- Open to semi-open

3.2 Low peat extraction landscape and peat polders (peat meadow)

The cultivated land in the lower west of Opsterland in the 16th and 17th centuries consisted almost exclusively of hay meadows. The very wet hay meadows downstream of the Koningsdiep flooded with some regularity. These were the bûtlânen. From the 17th century on, the landscape gradually changed. Also in this low-lying area, peat extraction started. This was accompanied by investments in water management.

3.2.1 Peatland landscape.

Peat extraction in the west of the municipality took place in a completely different way than in the bog reclamations. Dikes were built around the former hay fields in order to drain the area with a water mill. Peat could then be made from the top layer of drained peat. Only around 1750 the Gieterse method was applied in Friesland: A dredge was used to raise peat from below the water table. The dredged up peat was laid out to dry on peat dykes or banks. In the peat areas a system of peat pits and dams was left behind, which sometimes developed into peat ponds due to wave action.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Leidijken

- Pet holes and embankments (legacies)

- Dikes and cross dikes

- Culverts and laterals

- Peat Creeks

- Open

3.2.2 Peatland landscape

After the relatively profitable period of peat extraction, much unusable land remained. At first, individually sized peat fields were diked and drained to make the land suitable for hay or pasture. However, large-scale flooding led to drastic measures. Collectively, such as the Groote Veenpolder of Opsterland and Smallingerland, polder dikes (ring dike) with a ring canal were constructed. With windmills, and later with steam pumping stations, the water level was regulated and thus the land could be reclaimed, which often resulted in a very intricate strip parcelization.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Polder dikes (ring dike) and ring ditches

- Polder canals

- Water mills and pumping stations

- Fine-grained strip parcelization

- Predominantly ribbon development

- Open

3.3 Forest clearing landscape

The landscape of the forest clearings lies on the higher, relatively dry cover sand ridges. From the peat extraction areas, people sought out these higher areas and settled there because the land was becoming wetter. This created a predominant ribbon development (with sight lines between the buildings). Village centers often formed outside the ribbon. Agricultural yards are part of the ribbon development or are scattered along (sandy) paths and cross roads.

There are wide variations, from small-scale landscape elements, such as woodbelts, to robust landscape elements such as forest strips. Parcel planting consists of woodbelts, hedgerows, tree rows and forest strips. The transitions to the more open areas, the stream valleys, have a ragged character, as wooded banks and forest strips continue in varying lengths into the open area. The farmyards are often connected to the landscape because the plot planting of the farmyard continues into the adjacent landscape.

3.3.1 Forest clearing

As the peat oxidized with reclamation, people settled further and further away from the stream and eventually on the higher cover sand ridges. The elongated lots are perpendicular to the reclamation base often from the transition from the stream valley to the high cover sand ridge. With the settlement of residents came more planting in the form of forests, forest strips and other landscape elements. The infrastructure is formed by east-west parallel main roads with intensive access by (sand) paths and roads. On the highest part of the cover sand ridge lies the inner road (Binnenwei) and the outer road (Bûtewei) lies on the transition from the ridge to the stream valley. The later, new land consolidation roads run parallel to the longitudinal direction of the cover sand ridge. The water structure consists of ditches and canals. Cultural-historical elements are dikes parallel to the stream courses and bell towers in the village ribbons.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Elongated lots, perpendicular to the reclamation base

- Infrastructure in east-west direction, later connections north-south

- Dikes parallel to the creek and chimes

- Open - enclosed, with elongated vistas

3.4. Heath Reclamation Landscape

Until the end of the 19th century, heathlands characterized the higher parts of the landscape. The heathlands were mainly found on the cover sand ridges and in the east of the municipality. In the late 19th century and in the first half of the 20th century, the heathlands were converted to pasture and arable land. With these clearings, parcellation was also rationalized. A good example is the heathland reclamation of the Voorwerkersveld near Bakkeveen (1910-1916), which was parceled out in blocks and where new farms arose. Another part of the heath land was planted with conifers. Many of these forest stands are still present. The remaining part of the heathlands has now been designated as a nature reserve.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Rational block subdivision and road construction

- Keuter ontginningen, reclamation farms

- Coniferous forests

- Relief

- Open and private

3.5 Estate landscape

Especially around Beetsterzwaag, several estates were created between the 17th and 19th centuries. In Bakkeveen there is talk of an estate around the Slotpleats. The estates were mainly founded by wealthy patricians who owed their capital to peat extraction. This planned landscape was largely grafted onto the existing structures of the forest landscape. Within these structures, beautiful gardens and parks were laid out near the manor house with adjacent extensive production forests including coppice and characteristic avenues.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Estates

- Park gardens with avenue plantings, rows of trees, water features, groves, wooded banks and canals

- (sight) lines and vistas

- Star forests, beechwood, 12 apostles

- Road and path system; Chain Avenue, Scherpschutterslaan, Freulesingel

- Garden structures, garden walls and fences

- Adjacent subdivision

- Water features and structures; Beetstervaart, Opvaart

- Relationship between estate structures and elements and landscape around them

- Production forests Estate forests

- Coppice culture

- Open - private

4. The Koningsdiep stream valley

The stream valley of the Koningsdiep runs from the upper east to the lower peat polders in the west of Opsterland. Today the stream valley runs as an independent unit, canalized, open and lower, along and through different landscapes.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- No access parallel to the creek. Crossings (bridges) in a few places.

- Open

- Channelized and partially meandering stream

- Being/is being established as a nature reserve

5. The land consolidation

During the second half of the 20th century a number of land consolidation projects took place in the Frisian landscape, including Opsterland. The land consolidation of and along the Koningsdiep is probably the most far-reaching. The upper reaches of the stream valley were normalized (less winding), land in the stream valley was levelled with the help of sand extraction and access to the area was improved by building a road. The spatial impact of such land consolidation is usually an improved accessibility of the land in combination with a rationalization (or increase in scale) of the parcelization. Historic allotment structures have therefore largely disappeared from the landscape.

Landscape and cultural-historical values / Core qualities

- Rational subdivision

- Land consolidation ditches

- Straight roads

- Land consolidation forests

- Open/closed

5.2. The villages: in the landscape and their characteristics

Within the municipality of Opsterland are sixteen villages and twenty-three hamlets. Many of these are of medieval origin. The name Opsterland first appears as early as 1395 as Upsaterland, in a charter of Frederick, bishop of Utrecht. Remarkably, the administrative boundary of Opsterland remained unchanged for centuries. The current municipal boundaries are still identical to the period when Opsterland was a grietenij (jurisdiction). Like many other Frisian grietenijen, Opsterland is part of a disintegrated old gouw. In this case the Boornegouw, which covered the east-west oriented valley of the Boorne, which is flanked on both sides by the cover sand ridges, which were partly covered with raised bog.

A grietij was governed by a grietman (judge and administrator) with fellow judges, who were also in charge of (part of) the administration of justice. The first mention of the presence of a grietman in Opsterland comes from 1471. In the following centuries, grietmen came from distinguished families such as Fockens, Lycklama à Nijeholt, Van Lynden, Van Boelens and Van Teyens. The old courthouse in the Hoofdstraat is a reminder of the important role Beetsterzwaag had within Opsterland. After the introduction of the municipal law in 1851, however, grietman were no longer appointed, but municipalities were directed by mayors. Section 2.1.A. "The landscape" describes the different landscape types. We have arranged the villages by landscape type. Below we give a short description for each village. In this way a better picture emerges of their specific characteristics, such as location and morphology, in combination with social and societal interpretations....

1. High moorland clearing landscape

1.1. Frieschepalen

Frieschepalen (Fryske Peallen) lies against the border with the province of Groningen, next to the villages of Siegerswoude and Ureterp. It lies on the main road from Bakkeveen to the A7 highway from Heerenveen to Groningen. The village had 1,015 inhabitants in 2021 and originated in the 18th century as a reclamation village in the raised bog area. The posts in the village name refer to the boundary posts along the border with Groningen. Frieschepalen was not named an independent village until 1953. Before then, Frieschepalen was part of Siegerswoude. From about 1660, the Grote Veenvaart to Bakkeveen was dug to exploit the fens in the northeast of Opsterland. At Frieschepalen, this canal with a leave and drawbridge made a bend to the southeast. A few houses and an inn stood there. The canal has been filled in and now the Tolheksleane is the main artery of the village, an avenue with beautiful oaks and buildings of mostly detached houses, a few farms and a small church with roof trumpet from 1928.

2.Low moorland clearing landscape and peat polders

2.1. Nij Beets

Nij Beets is a young regional village, founded by peat laborers. It originated when peat extraction began around 1860. The miserable working, living and living conditions of the workers were the breeding ground for a fierce social struggle. In Nij Beets, the history of peat extraction and what it meant for the peat workers and the landscape can be seen in open-air museum It Damshûs. The Polderhoofdkanaal runs through the village. This canal was opened in July 2015. It is part of the Turfroute (a cultural-historical sailing route across the canals where the peat ships used to sail along) and ends in the National Park De Âlde Feanen. Relatively many young families with children and youth live in the village. It had 1,670 inhabitants in 2021.

A groundwater extraction and drinking water production site is located between Nij Beets and the A7 to the south-east of the village.

2.2. Tijnje

Tijnje (De Tynje) is a residential village, located in the western peat meadow area of Opsterland. The village is close to nature reserve "De Deelen". In 2021 it had over 1,530 inhabitants. The original character of this agricultural peat extraction village was a road village. Tijnje is a Dutchification of the Frisian word tynje, which originally referred to a fish dam in a watercourse. Tijnje originated in the nineteenth century at the time of peat digging in the low moorland area in the west of Opsterland. Around 1800 the first peat diggers and dyers came to the area around Tijnje. The former Reformed church from 1921 on the Rôlbrêgedyk is unique as a concrete building because of its architecture and construction, and it is on the monument list.

The establishment of the cooperative dairy factory "Volharding II" in 1916 was of great importance for Tijnje. It can be considered the end of the peat extraction industry. A healthy middle class developed afterwards with a wide range of often one-man businesses. These varied from blacksmith to wheelwright, from baker to butcher, from café owner to grocer, from shoemaker to bicycle maker, from house painter to carpenter.

After World War II, money became available to modernize the village. Around 1955, the ravines were filled in favor of a bypass road. Even the centuries-old Wispel was closed. Part of the equally old Moerdiep was narrowed and straightened. Tijnje then lost much of its original character in favor of land consolidation, intensive farming and labor relief.

In the same period, the A7 between Heerenveen and Drachten was constructed as a flat two-lane road. It made Tijnje much easier to reach, which certainly benefited the village's economic growth and prosperity.

2.3. Jonkersland

Jonkersland (Jonkerslân) is located on the southern edge of the municipality of Opsterland, on the road from Gorredijk to Langezwaag. The village was a hamlet of Langezwaag until 1988, but then became independent. The village subsequently expanded to include the small neighborhood of Feanborch. With just under 300 inhabitants, Jonkersland is the second smallest village in the municipality of Opsterland. The village can be typified as a regional village without a clear village center. Living is the main function of the village. The core of the village is more or less determined by the location of the village hall and elementary school. The village has an active population. The inhabitants together maintain 18 associations, committees and working groups, which deal with all kinds of facets of quality of life in the village.

2.4. Luxwoude

Luxwoude (Lúkswâld) is originally a peat extraction village and belongs to the smaller villages of the municipality. In 2021, it had 430 inhabitants. The village is characterized by ribbon development along the Hegedyk, the Alde Leane and the Lúkster Heawei. The main function of the village is living. Luxwoude is located in the west of Opsterland in the peat reclamation landscape. Luxwoude was for a long time the smallest village of the grietenij Opsterland. In 1749 only three families lived there and it had only ten voting inhabitants. At the end of the eighteenth century the number of inhabitants increased due to peat extraction in the area. Luxwoude never had a church and in the 16th century belonged ecclesiastically to Gersloot in the adjacent grietenij Aengwirden.

East of Luxwoude and the A7 is a (proposed) Groundwater extraction and drinking water production site.

2.5. Langezwaag

Langezwaag (Langsweagen) is located on the road from Gorredijk to Heerenveen, in the southwestern tip of the municipality of Opsterland. In 2021, the village had 1,050 inhabitants. The village also includes the hamlets of Nieuwe Vaart and Wijngaarden (partly). The village Jonkersland was also a hamlet of Langezwaag until 1988. Langezwaag lies on the border between sandy and peaty soil. To the west and south of Langezwaag there is an open landscape and to the east and north the landscape has a closed character.

The name Langezwaag is related to the location of the land. Elongated lands (zwagen) used to run from the small river Oude Ee in the north to beyond the Skoatterlânske Kompanjonsfeart in the south. Langezwaag is one of the older villages in the municipality of Opsterland, a village of farmers, who mainly had to make a living from arable farming (rye and buckwheat); cows and sheep were mainly kept because of the manure.

3. The forest clearing landscape.

3.1. Beetsterzwaag (country estate landscape).

Beetsterzwaag (Beetstersweach) is a village in the heart of the Frisian Woods. Beetsterzwaag used to be a village with prestige. Not for nothing is the village also known as the 'Wassenaar of the North'. Although it is not the largest core of Opsterland, the town hall is located there. On January 1, 2021, the village had 3,610 inhabitants. Several monumental buildings and gardens in the Hoofdstraat, which is at least three and a half centuries old, are silent witnesses to the wealthy noble inhabitants in the 18th and 19th centuries. The gardens at the estates, once the enjoyment of a few, are now open to all. Beetsterzwaag has 46 national monuments and is also a lively village. Historical riches are combined with contemporary attractions: restaurants, stores and boutiques, hiking and biking opportunities in the woods and many art galleries.

3.2. Olterterp (estate landscape).

Olterterp, east of Beetsterzwaag, is the smallest village in the municipality with about 90 inhabitants in 2021. The village also includes the hamlet of Heidehuizen.

Olterterp has a church from 1415 with a tower from the 18th century. Olterterp occurs in 1315 as Utrathorp. Utrathorp, together with Ureterp then called Urathorp, forms a pair of names indicating the location of the two villages in relation to the river Boorne. The Old Frisian ûtere means "outer" or "located on the outside," Olterterp is thus the downstream village.

3.3. Gorredijk

Gorredijk (De Gordyk) is the largest village in Opsterland, with 7,415 inhabitants in 2021. The village has a center function for the surrounding villages, with a high level of amenities. It is also of regional significance because of its shopping stock, small and medium-sized businesses and employment opportunities.

Gorredijk was created by peat extraction. The meaning of Gorredijk derives from the so-called "Vlecke", where goods were imported, stored and traded in the past. In Gorredijk, especially a lot of peat was transported. A clearly visible reminder of the time of peat extraction is the Opsterlânske Kompanjonsfeart (Opsterlandse Compagnonsvaart) which runs right through the village. This canal is part of the Turfroute, a beautiful recreational boating route, which especially in summer provides a pleasant bustle in the village.

Gorredijk is originally a ribbon village along the Opsterlandse Compagnonsvaart with the main streets being the Brouwerswal, Kerkewal, Molenwal and Langewal. The canal is crossed by the Hoofdstraat. Neighborhoods such as Leantsje, De Helling and De Vlecke were built in the early 1970s. In the 1980s, streets like the Spinnery, Brewery, Wolkammerij, Weverij, Mouterij and Kuperij were developed. More recent residential neighborhoods include Trimbeets and plan Loevestein, completed in phases. The latter brings Gorredijk and Lippenhuizen closer together.

The village also includes the hamlets of Oosterend and Kortezwaag. Kortezwaag (Frisian: Koartsweagen) was an independent village from 1315 until 1962. After that, Gorredijk and Kortezwaag formed a double village as Gorredijk-Kortezwaag, but after some years it was decided to shorten this to Gorredijk and thus the older Kortezwaag became a hamlet of Gorredijk as of 1969. The hamlet Kortezwaag is usually counted from the sports field complex Kortezwaag with the habitation on De Leijen, the Dwersfeart and the connecting stretch of the Nijewei between De Leijen and the Dwersfeart.

3.4. Hemrik

Hemrik (De Himrik), is a small village in the south of the municipality of Opsterland. In 2021, the village had 755 inhabitants. The village also includes the hamlets of Hemrikerverlaat, Sparjebird (largely) and Welgelegen (small part).

The name comes from the Old Frisian hemrike and means marke; "common land" or "village area." In the vicinity of Hemrik the unique coulisse landscape can be found. The coulisse landscape consists of meadows with wooded banks (houtsingels). Various walking, cycling and bridle paths can be found in the area. Hemrik lies in the heath landscape and near the valley of the Koningsdiep. The village lies along the Opsterlânske Kompanjonsfeart (Opsterlandse Compagnonsvaart). Along the canal are characteristic and atmospheric lock keeper houses.

3.5. Lippenhuizen

Lippenhuizen (Lippenhuzen) is originally an agricultural village, formerly called Kobunderhuizen. In 2021, it had 1,300 inhabitants. Via the Compagnonsfeart, the village is connected to Hemrik, Gorredijk and Terwispel. This part of the Turfroute leads through a coulisse landscape (stream valley and sand ridge cultural landscapes). On foot or by bike, the landscape can also be admired. A nice excursion is the Liphústerheide, a beautiful heath along the Koningsdiep.

3.6. Terwispel

Terwispel is located in the west of the municipality of Opsterland, close to Gorredijk. In 2021, it had 1,000 inhabitants. The village also includes the hamlet of Kooibos. It is located near a wooded area. It belongs to the older settlements of the municipality and originally has an agricultural character.

Terwispel is one of the older settlements of the municipality. The village lies on the border between two landscape types. To the west of the village lies the open landscape and to the east the coulisse landscape. There is a hybrid form of a road village and a watercourse village. The road "De Streek" and the water "De Nieuwe Vaart" form a junction along which the village has developed.

3.7. Ureterp

Ureterp (Oerterp) is one of the older farming settlements on the higher sand ridges north of the Koningsdiep River. In 2021, Ureterp had 4,860 inhabitants. Relatively many commuters live in Ureterp, a result of its convenient location in relation to Drachten (6 km), Drachten, the A7 and the N381.

Despite its proximity to Drachten as a nurturing core, Ureterp has a nurturing function for the surrounding villages (Frieschepalen, Siegerswoude and Wijnjewoude). Ureterp is the second village in the municipality of Opsterland after Gorredijk.

Ureterp is a road or regional village, which unlike other road villages was not created by peat extraction. Its elongated shape is a result of its location on the cover sand ridge between the original Drait and the Koningsdiep. The first habitation took place on this sand ridge and must have been at least a thousand years old. The name Ureterp (Urathorp, with the Frisian oer = above) is explained by its location in relation to the Koningsdiep. Ureterp lies upstream. Terp thus means village here.

3.8. Wijnjewoude

Wijnjewoude (Wynjewâld), like Ureterp, is one of the older farming settlements in Opsterland. The village had 2,055 inhabitants in 2021. The village lies between Bakkeveen and Hemrik near the eastern border of the municipality. The village also includes the hamlets of Klein Groningen, Moskou (partly), Petersburg (partly), Sparjebird (partly) and Wijnjeterpverlaat.

Duurswoude and Wijnjeterp were two regional villages formed in the late Middle Ages in each other's line on a sand ridge between Koningsdiep and Tjonger. They were merged into the village of Wijnjewoude in 1974. The surroundings are park-like and invite recreation. Wijnjewoude has several campsites, mini campsites and nature campsites. The woods east of the village were laid out in the second half of the 19th century by order of the Lycklama à Nijeholt family. There are many walking and cycling routes through the greenery; the pearl being the Duurswouderheide between Bakkeveen and Wijnjewoude. It is the largest heathland of Fryslân, with pingoruïnes (dobs). Wijnjewoude also lies with Klein Groningen on the Compagnonsfeart, and thus along the Turfroute.

4. Heath Reclamation Landscape

4.1. Bakkeveen

Bakkeveen (Bakkefean) is a village near the three-province point of Friesland, Groningen and Drenthe. The village had 1,905 inhabitants in 2021. A special piece of Friesland where forest, heath and dunes predominate. Near Bakkeveen are the Bakkeveense Duinen. This is a heath and forest area untouched by the peat extraction in the 19th century. Two centuries ago, all of southeastern Friesland looked like this. The only sheepfold in Friesland is located on the adjacent heathland of Allardsoog and the heathland of Bakkeveen. Bakkeveen lies in the eastern basin of the Koningsdiep, which rises northeast of Bakkeveen. The stream valley of the Koningsdiep is being redesigned whereby the stream will regain its original meandering course. Three organizations manage the nature reserves around Bakkeveen: Natuurmonumenten, Staatsbosbeheer and It Fryske Gea. Bakkeveen also has a country estate, De Slotpleats, with associated forest. This also ties in with the country estate landscape.

The village also includes part of the hamlet of Allardsoog and a piece of the village of Waskemeer. It is located in an area with vacation parks and there are many opportunities for recreation. There is an outdoor swimming pool and the largest maze park in the Northern Netherlands.

Bakkeveen is also a commuter village; many inhabitants are oriented for work to places like Drachten, Leeuwarden, Heerenveen and (to a lesser extent) Groningen and Assen.

4.2. Siegerswoude

The village of Siegerswoude (Sigerswâld) is located in a semi-open to open bog reclamation area, on the border between the source area of the Koningsdiep River and the northern sand ridge. In 2021 Siegerswoude had 835 inhabitants. There used to be three residential areas, in the north a hamlet near the entrenchment developed into the independent village Frieschepalen. In the south, Bakkeveen became an independent village. And in the middle, It Foarwurk, today's Siegerswoude came into being. In the Middle Ages there was an outpost of the monastery of Smalle Ee. Peat extraction meant a new boost for the area. The original center is now the junction with the Bakkefeanster Feart.

Siegerswoude has three residential areas: the village proper on the Binnenwei and by extension the Bremerwei, the hamlet of Voorwerk up to De Wilp and the northwest corner between Frieschepalen and De Wilp, along the canal and the Langpaed.

5.3. The people: The DNA of the Opsterlander; the uniqueness of the population

1. Opsterland identity

Opsterland's uniqueness lies not only in the diversity of its landscape types, its inhabitants and villages also have their own qualities. The developments that occurred in the landscape and the living and working conditions of the population have left their traces in the landscape and contributed to the formation of the identity of the residents in the various villages. The Frisian language is an important unifying factor within Opsterland's sixteen villages and twenty-three hamlets. The village character of the municipality is cherished by residents and the 'us knows us' is characteristic of the village culture: people greet each other on the street, there is togetherness and a strong social bond. The inhabitants of the villages are proud of their own village and their past and they feel connected to the special characteristics of the landscape, both natural and man-made.

Important for the recognizability and the Opsterland identity, in addition to the landscape, are the cultural-historical valuable and monumental buildings, such as the keuterboerderjes, the stately buildings of Beetsterzwaag and the estates of Olterterp and Bakkeveen, the churches, coach houses, school buildings, characteristic farms and workers' dwellings, and other cultural heritage such as bell towers, grave monuments and boundary posts. In addition, our "soil archive" still contains many traces, both visible and invisible. They show how people in Opsterland used to live and work. Identity is also formed by intangible heritage, such as stories of and about the past, by artistic expressions such as music and theater, by crafts, customs, traditions and celebrations. They provide a sense of connection with previous generations and are worth passing on to generations that follow.

2. The oldest settlements on the Koningsdiep.

Opsterland is part of region the Frisian Woods. The name Opsterland comes from the former Old Frisian name Upsaterland. It possibly refers to the inhabitants who settled in settlements on the higher sand ridges above and below the Koningsdiep, also known as the Alddjip or the Boorne, and on the higher area on the tributary the Wispel. Archaeological finds show that habitation already existed during the Old Stone Age,[2] the best known archaeological find in Opsterland is the Wijnjeterp fist axe found in 1939, which has an estimated age of 100,000 years. In addition, numerous flint sites have been found, including near Ureterp, Bakkeveen and Siegerswoude. Finds consist of arrowheads, fishhooks, scrapers and other tools belonging to the Hamburg, Magdalenian and Creswell cultures (young Paleolithic cultures from the period 35,000-10,000 B.C.). Several sites are also known from the Middle Stone Age (ca. 10,500 B.C.-ca. 6,000 B.C.), for which small flint tools are characteristic. In addition, there were several burial mounds in Opsterland. During the Bronze Age (2000-800 BC), the presence of inhabitants seems to disappear. It took until probably the late tenth century before residents settled again. Archaeological finds from more recent periods show that from then on habitation in Opsterland was an ongoing process: in Siegerswoude the remains of an iron smelter were found, and near Bakkeveen, Siegerswoude and Nij Beets traces of medieval homesteads with peat pots and firing places (with remains of ball pots) were found.

Settlement was mainly concentrated along the Boorne River. It has been shown that in several places there was an old cemetery; this was the original location of the settlements. However, the habitation gradually moved further and further away from the river, creating the characteristic ribbon settlement with more concentrated habitation here and there: today's villages. The ribbon of villages situated above the Boorne consisted of Beetsterzwaag, Olterterp, Ureterp and Siegerswoude, the ribbon south of the Boorne of Terwispel, Lippenhuizen, Hemrik and Wijnjewoude. The towns of Luxwoude, Langezwaag, Kortezwaag formed a smaller ribbon on the Wispel. The villages each have their own character and history, so there is not only an Opsterland identity, but also different village identities.

3. Opsterland identity and village identities.

Words that fit Opsterlanders are entrepreneurial, self-reliant, down-to-earth and modest. People are honest, trustworthy, straightforward and sometimes a bit stubborn. There is a mentality of getting things done and, especially in the smaller villages, of 'doing things together'; residents feel responsible for the quality of the living environment and are happy to contribute to the availability of various facilities. Many facilities in the villages are managed by residents of the villages themselves, such as various sports facilities, village halls and (natural) swimming pools. The residents of Luxwoude even jointly maintain the hundred-year-old gliding carousel used annually during the village festival. Opsterland has strong social structures and its inhabitants form a close-knit community. People from different layers of society know each other through the many sports, music, singing, and drama associations. Terwispel, consisting of about 1000 inhabitants, has as many as 12 neighborhood associations.

Besides similarities, there are also differences, not only between the eastern and western parts of Opsterland, but also within the villages themselves, stemming from their own local history. For example, Beetsterzwaag has traditionally been the seat of the Opsterland administration. Beetsterzwaag was already in the Middle Ages the center of the grietenij Opsterland.

Noble and patrician large landowners left stylish country houses and extensive forests in and outside the village. Olterterp was almost entirely owned by the Van Boelens family in the eighteenth century. The Redbeard gardens in both villages are known far beyond the municipal boundaries. Because of its good accessibility via the A7, Beetsterzwaag has in recent decades become a sought-after residential location, where commuters also settle. There is an active club life and residents feel very involved in the ups and downs within the village. Much is taken up in the areas of recreation and culture, in which the history of Beetsterzwaag regularly plays an important role. Moreover, Beetsterzwaag is popular among visual artists, as evidenced by, among other things, the annual art market, various (temporary) exhibitions and art house SYB, which encourages young artists in their talent development. The housing and living conditions of the population in particularly the well-to-do Beetsterzwaag and Olterterp contrasted with the way of life in the poorer villages in the immediate vicinity and the villages that arose as a result of the peat reclamations.

4. The peat villages

In the parts of the municipality where villages arose from the peat, such as Nij Beets and Tijnje, living conditions were generally poor. Poverty prevailed and the population lived in meager dwellings, sod huts or wooden huts. The population relied heavily on each other. Peat laborers in the peat villages located in the western part of the municipality regularly organized peat revolts with the aim of forcing better wages. The poor living conditions of the population were reason for preacher Ferdinand Domela Nieuwenhuis (1846-1919) to work to improve their lot. The socialist ideas that he proclaimed during his visits to Nij Beets, among other places, would have an important place among the local population; it created solidarity and connection. The social character is also evident in Nij Beets today. There are numerous associations, an annual village festival and 'boartersdei' for the children are organized. The inhabitants of Nij Beets cherish their past and knowledge of the village's history is kept alive. The open-air museum It Damshûs also plays an important role in this. The harvest event Stoppeldei, which has been organized every year since 2008, also emphasizes the past: among other things, old crafts, eel smoking, the sale of regional products, ring stabbing and antique agricultural machinery take center stage.

Like Nij Beets, nearby Tijnje originated as a peasant village. Thanks to reclamation, the reclaimed land could be used by cattle farmers, small cow milkers and householders (smallholders with a few head of small livestock who were also employed by a larger farmer). From an economic point of view, the establishment of the cooperative dairy factory in 1916 was of great importance to Tijnje. There was a lot of cooperative organizing in the village, by both farmers and later shopkeepers. In Tijnje, mutual togetherness and community spirit still play an important role. A healthy middle class developed with a multitude of often one-man businesses, and Tijnje was thus a self-sufficient and active village with a close-knit community. Today, the active, independent and "going for it together" still characterizes Tijnje and its residents. Several village festivals are organized that are unique to this place, as well as annual winter festivals with a fair. Also special is the carnival association that has existed for decades. Shaping supports for the village's identity are the preserved ones such as the dairy factory, the war memorial on the general cemetery, the many farms, some historical buildings on the village's main road, the boulder, the water mill at the Uilesprong and the mill without sails.

Peat from the low moorland was transported to different parts within the Netherlands. Traditionally, the "vlecke" Gorredijk, now the largest town in Opsterland, played a central role in peat extraction, as a place where goods were imported, stored and traded, and as a transit port of peat to Amsterdam, via the Opsterlandse Compagnonsvaart. Here, too, living conditions were austere. The inhabitants of Gorredijk were active entrepreneurs and adept at doing trade as early as the seventeenth century. For this reason, the people of Gorredijk were nicknamed 'handjeklappers'. These characteristics can still be found in today's Gorredijk as well: Gorredijk is a place with an active entrepreneurial climate, organizes two large annual fairs each year and also has a commodity market every Wednesday afternoon. Active entrepreneurship, commercial spirit and a mentality of perseverance is characteristic of the inhabitants of Gorredijk. The southern villages of Luxwoude, Jonkerslân and Langezwaag, initially villages consisting of only a few farming families, owe their expansion to peat extraction and peat mining.

Although Frieschepalen and Siegerswoude are located in the east of the municipality, these villages also have their origins in peat extraction. They originated in the eighteenth century as reclamation villages in the raised bog area; here, too, the population lived in great poverty. Frieschepalen, however, existed much longer and, before the peat mining caused village formation, was part of the Frisian water line. Frieschepalen had an entrenchment in earlier times. The entrenchment was partially rebuilt in 2014 and serves as a "lieu de memoire"; a place of remembrance, where people are made aware of a special point in the landscape. The socialist aspect that was of great influence on the peasant villages in western Opsterland was less present in Frieschepalen and Siegerswoude. In villages in the northeastern part of the municipality as well as in Wijnjewoude, religion played an important and unifying role in the daily life of the villagers. Especially in Ureterp, religion determined the social structure within the village. Religion is still very important in all these villages today. In Ureterp, the inhabitants also maintain their contacts among themselves intensively through the 13 sports clubs and the 11 singing and music associations.

Some villages have become true commuter villages in recent decades. With the arrival of the A7, and with it the convenient location in relation to Heerenveen or Drachten, the character has changed. Especially Beetsterzwaag, Gorredijk, Ureterp, Wijnjewoude and Bakkeveen are popular among people who work both inside and outside the municipal boundaries. Thanks to the developments of the last decades, the Opsterland population is a mix of born and bred Opsterlanders whose ancestors had their roots here and 'newcomers' who settled in one of the villages because of their work and the and attractive living environment.